The sign on the coastal road had long ago given up the name of the town. Salt had chewed the paint to bones; everything here tasted like old iron and rain.

Ace stood on the verge, coat flapping, eyes half-lidded as if listening to something under the wind. Mai popped the glovebox of the battered sedan and took out a cracked field scanner, the kind that never sat still at zero. Its needle quivered like a nervous thought.

“Resonance,” Mai said. “Not a spike. A seam.”

Ace tilted her head. “You feel it, or are you just pretending to keep up with my mystique?”

Mai flicked the scanner. “If I wanted mystique I’d buy you a taller pair of boots.”

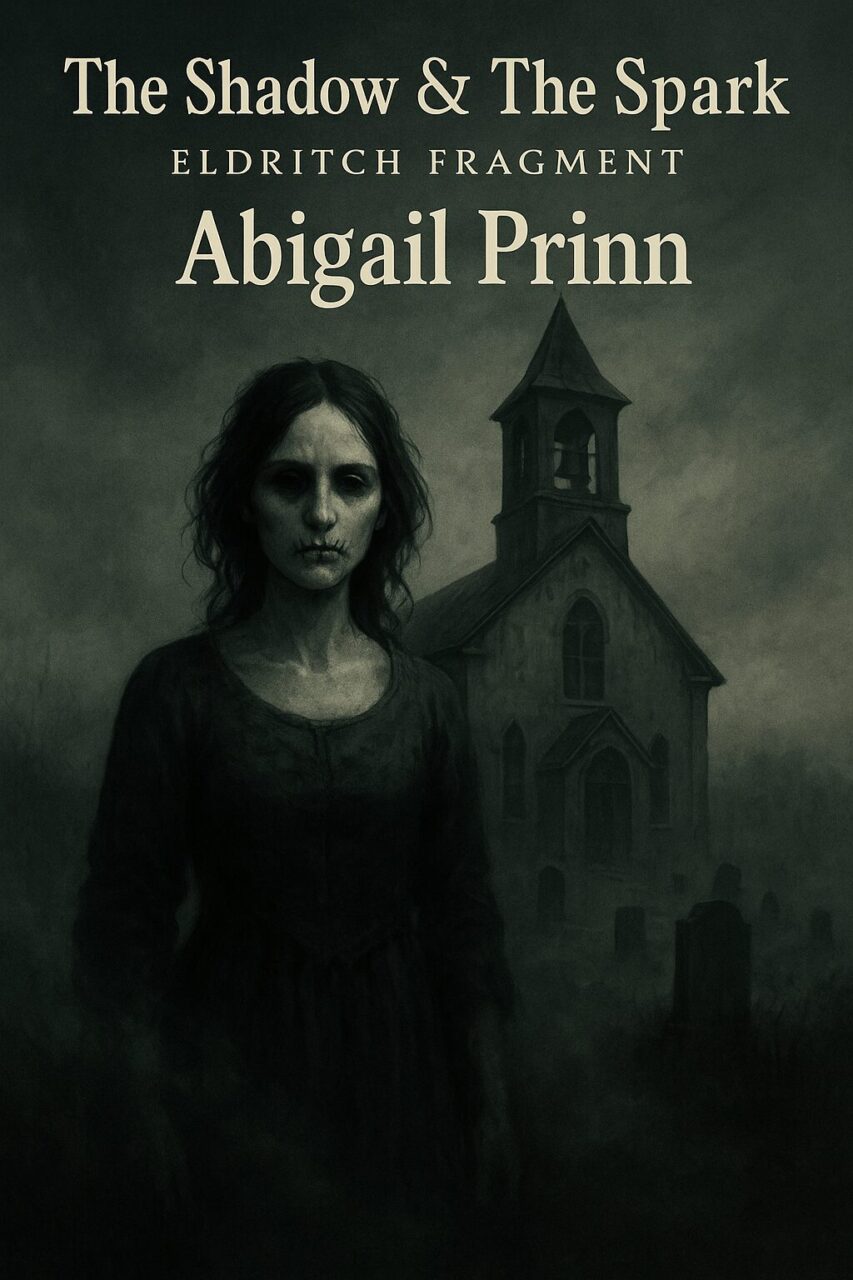

Ace smirked and turned toward the drowned outline of the church. It sat at the crown of the town like a forgotten verdict—shingled tower, black windows, the sea pressing a flat gray palm against everything. The closer they got, the stronger the seam felt: a hairline crack in the air’s temper, something that made the gulls veer and the grass lean.

The first local they encountered had the careful silence of someone who’d already told this story too many times. The grocer’s bell chimed like a cough when they entered; the man behind the till did not look up.

“We’re not selling,” he said.

“We’re not buying,” Mai answered. “We’re passing through. Looking for the church.”

“People pass through,” the grocer said. “They don’t look.”

Ace grazed a fingertip over a jar of candy sticks, felt the useless sweetness crumble under the label. “How many days?” she asked without turning.

His eyes flicked to her, then to the window. “Three until the equal night,” he said softly. “And one before that for the warning.”

“Any names circulating?” Mai asked.

The man hesitated. Names had weight here. “We don’t speak it.”

Mai slid a twenty across the counter anyway, then a second, then a third. “I’m not a priest,” she said. “And she’s worse.”

That got the smallest crack in him. He glanced at Ace, failed to place her height, her shadow like a second tide. “There was a woman,” he said. “Before the town was a town. When the trial fires burned. They say her grave is under the bell. They say the bell never rang for her.” He swallowed. “They say she taught her uncle the part he didn’t dare write.”

Mai nodded. “Abigail.”

The man winced, as if the name had teeth. “The night it first happened,” he murmured, “the fog came inland like a herd. It pushed through the streets. The bell rang by itself. Only once. And then someone saw a hand in the fog, reaching for the tower steps.”

Mai pocketed the scanner and the grocer’s eyes followed the movement like it might erase the last hour. “We’ll try not to make a mess,” she said.

“You can’t clean this,” he said. “You can only survive it or not.”

Outside, the sea threw slow sheets of rain. Ace lifted her face to it, eyes closed, letting the cold find skin. When she spoke, it was not to Mai.

“You’re quiet,” she said, and if the word had a direction, it was aimed inward.

The answer came as a breath in her bones. Not a voice, not at first. A pressure like a palm on a locked door.

Then, as the wind stuttered: Let me listen.

“Violet wants to eavesdrop,” Ace said.

Mai’s mouth flattened. “Tell Violet we charge consulting.”

Ace’s smile was a cut. “She’s bad with invoices.” She pointed at the church, where a blue-black gull had landed on the cross and seemed to be pecking at rust like it could draw blood. “We start there.”

The church smelled like wet paper and salt. Every hymnbook was bowed like a supplicant. At the rear, a ladder led to the bell deck. Mai’s scanner went from quiver to tremor.

“Not a seal,” she said. “A circuit.”

Ace’s eyes found the chalk marks on the nave floor—most scrubbed away by time and panic, but some lines had eaten into the wood as if the chalk had been acid. She traced one with her boot. The pattern made no sense and every sense at once. It ran toward the altar and dissolved at the baseboards like a map that refused to give up what it knew.

The whisper in her was clearer now, a violet shimmer against the quiet.

They stitched themselves here, said the echo inside her. Threaded the night through the bell and the bones. A girl who hated the way men said her name.

“Abigail,” Ace said.

Mai crouched, tugging at the lip of a loose floorboard. It came up with the resignation of a scab. Under it, she found a tin, its lid sealed with wax that had long ago sweated and re-hardened into the look of old fat. She cracked it with a screwdriver’s sigh.

Inside lay a coil of yellowed vellum, hand like a thorn bush. Latin bent wrong. Little sketches of a woman’s hand and a bell with a mouth that wasn’t metal.

Mai’s lip curled. “De Vermis Mysteriis,” she said. “The remix.”

“She improved on it,” Ace said. “Or ruined it.”

“Both can be true.” Mai lifted a page closer. The ink bled at its own edges. “This is a resonance tether. She’s split herself.”

“Where’s the other half?” Ace asked.

Mai tapped the bell tower with her eyes. “Where you’d make yourself heard.”

They ascended into damp. The bell hung there, unremarkable until you saw that the clapper had been wrapped in human hair. The braid had weathered to a kind of rope, a guttered candle had dripped down it at some point, and something had charred the rim where the clapper would have kissed. A small nest of charms and sea glass sat in a corner, mice-scattered, and a child’s shoe waited beside it like an apology.

Mai reached for the braid. Ace caught her wrist.

“You okay?” Mai asked.

“I don’t like the way it’s looking at you,” Ace said.

“It’s a bell,” Mai said.

“It’s a mouth,” Ace corrected.

She found the cut marks on the wood beam: notches counting some passage of time, then a double notch, then the wood had been burned. The wind shoved at the louvers with the whine of old teeth.

In her mind, Violet had placed both palms on the door now. It would be better to leave this, the echo said, and the angle of that sentence didn’t feel like fear. It felt like hunger disguised as caution.

“Of course you’d say that,” Ace murmured. She looked down through the louvers at the cemetery behind the church. Stones like wet knuckles. A row of yews that had learned to lean away from the sea. One stone tilted toward the tower, as if listening.

Mai unholstered the disruptor and checked its meter. The runes etched along its spine were dull in the rain light. “If the tether’s built to ride the bell’s harmonics, I can scramble it. But it’ll overheat.”

“Put a fan on it,” Ace said.

Mai lifted it until the runes caught some private frequency and began to glow, subtle and stubborn. The pistol hummed through the bell’s mouth and Ace felt the air thicken, like the room had been suddenly given weight. The hair-braid trembled.

Something inside the bell said a single word without sound: mine.

“You’re not,” Ace told it, and went back down.

They slept badly in the car, rain banding the windshield into uncertain stripes. At some hour that wasn’t exactly night and wasn’t yet morning, Ace’s eyes snapped open and she was looking at the crosshair of two cracks in the glass. Her breath plumed the way it would in winter. But the dashboard clock told her what the day thought of that.

The bell rang once.

It was not loud. It was the memory of loud, the echo of a blow that had landed lifetimes ago, leaking back into the present. The sound went through the town like a fingernail down a plate. A dog three streets over barked, then coughed, then whimpered into silence.

Mai sat up with her disruptor already in her hands. Ace’s own hands were empty, which meant nothing. Her blades belonged to her even when they were two dark lines across her back.

They ran.

At the foot of the tower, fog rolled its belly across the gravestones. The stone that leaned toward the church now had a slick new tilt; the ground under it had deflated. The name carved there had been eaten by lichen, but the dates were wrong, the way dates get wrong when a town tries to tidy a story after the story has eaten someone.

“Ace,” Mai said.

She didn’t have to say what. Ace felt it: the seam they’d sensed at the edge of town was a slit here, and the fog came out of it not as weather but as intention. It gathered against the tower door and massed into a shape that had the idea of shoulders.

A woman’s laughter came thin as thread stretched too far.

Violet was suddenly very close. She pressed her forehead to the other side of Ace’s skull, a private, intimate lean. She knows how to leave pieces. Ask her how it felt to give away what she didn’t want to keep. Ask her if you can borrow the trick.

“No,” Ace said aloud.

The fog convulsed. A hand formed—not flesh, not air, but something in between. It pushed against the tower door and sank through as if through a curtain. The bell up above tugged the sound down the rope of hair and the hair hummed like a fly’s wing.

Mai stepped forward and fired. The disruptor spat a flat pulse that was more absence than light. It slapped the fog-hand into steam, then it gathered again, slower, learning the shape once more with a stubbornness that felt human.

“Overheating,” Mai warned.

“You’re pretty when you glow,” Ace said, but there was no smile in it now. She drew one blade. Its edge came alive with that subtle green heat that was not fire but was always mistaken for it. The air made a small disapproving sound at the sight.

She cut the hand.

The fog reeled. Something inside the tower banged as if the clapper had jerked against the bell on its own. The town flinched all at once. A door slammed. A prayer started and ended with the same sound: oh.

The fog pulled back and ran for the graveyard.

It didn’t drift, didn’t amble; it sprinted, low and fast, pooling at the foot of the leaning stone as if the ground there had a mouth. Ace and Mai followed, their breath pumping white. The grass here was slick; it gripped boots like greedy fingers. The stone’s base shivered.

“Her tether,” Mai said. “The other anchor.”

Ace put her glove to the stone and felt something under it that had nothing to do with bones. The sense of a woman’s jaw set in the way jaws set when they’ll stand in a circle of men with ropes and say no again.

“Abigail,” Ace said softly. “They stopped your mouth. You taught your uncle how to write a louder one.”

A shape stood up out of the fog where a person might stand. She wore a dress the color of memory and eyes that were not eyes. Her mouth was sewn in the old way: with thread you could only see if you knew how not to look at it. When she spoke, she did it without it.

— Mine, she said again, and this time Mai heard it too because she flinched.

“Who?” Ace said. “The bell? The town? Your name?”

— The voice, Abigail said, and the fog made the syllables feel like stones in a pocket at the bottom of the sea. — He took it. He put it on a page. They burned me with a silence and he took my voice. I cut it out first. I kept the halves.

Mai’s face tightened. “Half with the bell. Half with the earth.”

Abigail looked at Ace. No—through her. Past her.

Violet rose like a bruise blooming under skin. She pressed her hands—hers, not Abigail’s—against Ace’s ribs like she could push a door out of a house. The world warped a degree. The blades’ green light guttered as if in wind.

Let me, Violet whispered. Let me speak to her. I can show you how to unmake a name without killing the throat. You’d like that. You’ve always liked that.

Mai stepped closer, voice very steady. “Stay with me.”

It worked. Some things always did. Ace’s breath decided to be hers again. She let the green hum fill the bone of her blade, not the blood.

“Abigail,” she said, “we can cut the tether. But it’ll burn. When the link breaks, the part you buried will be all that’s left. It will still be yours. It won’t be anyone else’s.”

— I won’t be enough, Abigail said. — I am only the half that learned to be quiet.

Mai lifted the disruptor. Its runes were nearly white hot, lines breathing like an overworked lung. “Then we teach you to be loud the old way,” she said. “We ring your bell.”

Ace laughed, once. “She’s good,” she told the fog. “She’s always been good.”

They ran the line: Mai up the ladder into the tower, Ace in the cemetery with her blade laid flat against the stone, its edge pressed to the seam in the soil that had learned the shape of a mouth.

At the top, Mai pulled the braid of hair down into the disruptor’s muzzle. It smoked and stank—the smell of an old brushfire and a barber’s floor. The pistol’s hum found the bell’s shallow note. For a second they disagreed, and then the world chose a third sound that made every nail in the church remind you it was iron.

“Ready!” Mai called.

“Do it,” Ace said.

The first strike was not hers. The bell hammered the town and the fog with sound, and sound became a tool. It rattled the windows in their frames and shook out prayers that had been waiting under tongues for centuries. The fog staggered, then tried to pull back into the earth. Ace’s blade met it there, edge kissing dirt, green light eating wet. The tether that was not a rope but behaved like one snapped. When it did, Ace felt a whiplash go through her arms and up into her heart. For a heartbeat she wasn’t sure she’d gotten all the way back into herself.

Violet screamed in her skull. Not a word. Not a threat. Something older. Then she was gone to the edges again, behind the door where she sometimes paced in the dark.

Up top, Mai screamed too—hers was only human. The disruptor’s casing glowed like a horseshoe. She slammed its butt against the bell and the second strike was different, as if the bell had learned to hit back. The braid of hair caught fire in a lazy, almost bored flame. It burned the way old promises burn.

In the cemetery, the fog-woman arched. The thread at her mouth smoked and popped. Ace stepped forward, blade down, and said, “We’re giving it back.”

— Which part? Abigail asked. — The voice or the name?

“Both,” Ace said. “If it kills you, you get to choose that too. But I don’t think it will.”

Abigail’s eyes, which were only the idea of eyes, turned to the stone that had listened. She did not nod. The thread split. The fog collapsed but did not vanish; it redistributed itself into the air they had to breathe, which meant they would carry it for a while whether they wanted to or not.

The bell rang once more, entirely by itself. Clean, this time. A sound that had been waiting.

Silence fell in the way only coastal places know, where even the sea holds its tongue for a count.

Mai came down the ladder, disruptor in her hand like a bird she’d kept alive by speaking to it. Her hair stuck to her forehead in silver ropes. Sweat made her eyes look like they’d been cut deeper.

“Tell me we didn’t just free a murderous revenant with a grudge and a manual,” she said.

Ace looked at the stone. The tilt had corrected itself by the smallest degree. The soil around it steamed. “If she wanted blood, we’d have given her a bell,” Ace said. “We gave her a choice.”

Mai looked like she wanted to argue with that, then didn’t. She holstered the disruptor with the delicacy you use when you put a sleeping child down.

They stood for a long minute, listening to the town decide whether to resume pretending.

A door opened. The grocer came out, walked a few steps, then stopped as if he’d come outside to check the weather and forgotten the word for sky. He saw them and raised his hand halfway, a gesture honed in a place where you learn to thank people without making them stay.

Ace raised hers back. The exchange was a treaty no one had written.

They went to the car. The rain had decided to be rain again. Mai cracked the window, let the clean air burn the last of the bell-smoke out of her nose.

“You okay?” Ace asked.

Mai snorted. “Ask me in an hour when my pistol stops making whale noises.”

“You do know what whales are,” Ace said.

“Big sadness tubes with songs,” Mai said. She rested her head back, eyes closed. “You okay?”

Ace watched the church in the rearview. The tower sat like a tooth in a jaw the sea had been gnawing for a century. “Violet wanted in,” she said.

“She always wants in,” Mai said softly.

“She was scared,” Ace said.

That opened Mai’s eyes. “Of Abigail?”

“Of the idea you can split yourself and still be whole,” Ace said. She made a small, sharp sound that wasn’t quite a laugh. “She’s always believed in halves.”

Mai reached across the console and found Ace’s wrist. The touch wasn’t dramatic. It didn’t need to be. “I don’t,” she said. “Not with you.”

They drove. The town thinned to scrub, scrub to shore, shore to the long indifferent road. The rain dimmed. The sky pretended to consider a color.

At the next bend, Ace lifted a hand to her ear though no device sat there. The habit of people who listened to things that didn’t use frequencies you could rent.

In her head, behind that closed door, Violet moved again. Not pacing. Sitting. Sometimes the echo could be petulant, a curled cat with knives. Now she sounded like an empty room that remembered a piano.

You’ll look for the uncle, Violet said, as if she were offering a weather report. You can’t resist a man who binds a voice to paper and then sells the paper as a god.

“Ludvig can wait,” Ace said. “We’ve got streets to fracture.”

Mai eyed her. “Talking to your imaginary friend again?”

“Always.” Ace angled a look at her, all smirk and softness at once. “Don’t be jealous.”

“I’m not,” Mai said, then bit the corner of her mouth like she’d said too much of the wrong thing and decided to own it. “She’s the shadow. I’m the spark. Shadows don’t burn.”

“They also don’t blind,” Ace said.

The road unspooled. The sea kept pressing its patient hand. The town disappeared behind them, then reappeared only as sound: at their backs, the bell rang once, a single clean note, like someone laughing without bitterness for the first time in a long time.

Days later, a rumor would pass along that coast like the wind trades gossip with grass. People would say the bell had rung with no hand. Someone would swear they saw a woman in old clothes walking toward the edge of town and that her mouth was the kind of scar books can’t teach you. A boy would lift a floorboard in his father’s house and find nothing under it and feel relieved for a reason he would not be able to explain until he was old.

Ace and Mai would be elsewhere by then, standing in a city where the neon bit your teeth and the alleys recognized your shoes. But that night, as they found a motel that had learned to mind its own business, Ace lay on the thin mattress listening to the air conditioner wheeze and the darkness settle like a familiar coat.

Violet did not come closer. She sat where she sat and thought her strange thoughts. For once, Ace did not open the door. For once, the quiet between them felt like a pact rather than a countdown.

In the morning, when they pulled onto the highway, Mai touched the dash like people touch an altar.

“Where to?” she asked.

“Anywhere loud,” Ace said, and the car agreed.

Want to read more this kind of stories? Buy me a coffee!